We have all heard that an economic recession is imminent, because, after all, the Fed is tightening aggressively, and we have an inverted yield curve. On top of that, the stock market has fallen all during 2022, an indication which economist Paul Samuelson famously quipped back in 1966 had “forecasted 9 of the last 5 recessions.” But the unemployment rate in September 2022 was still low at 3.5%, and the latest preliminary GDP numbers out for Q3 2022 show that the economy is still growing. So where is the recession that all of these omens have promised us?

Like baking a cake, baking up a recession takes time, and, except for an event like COVID with the government shutting down the economy, things happen at the right time. So how can we know when that is?

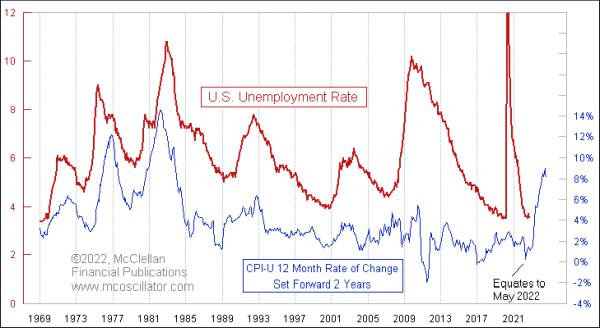

This week’s first chart shows one way of getting at that timing. The main feature of a recession that gets everyone excited is that people lose their jobs, and the unemployment rate rises. The movements in the unemployment rate tend to echo the similar movements in the CPI inflation rate about 2 years later. The inflation rate bottomed in the middle of 2022, just before Congress and the Fed started throwing money at the COVID problem, with predictable results. We are now at the echo point of that inflection in the inflation rate. The rise in inflation over the 2 years since then should bring a corresponding rise in the unemployment over at least the next 2 years.

The lowest point for the CPI rate of change was in May 2020, so, ideally, that should have meant a bottom for the unemployment rate in May 2022. But that was a momentary spike low, and the 2-year lag is never exactly precise anyway. So setting a stopwatch and expecting precision is demanding more from this model than it typically lives up to.

We can also get timing information from another source, which is public opinion. It turns out that the public’s mood turns sour before the economy does. Here is a comparison of the unemployment rate to the University of Michigan’s Index of Consumer Sentiment. These sentiment data are plotted on an inverted scaling, and shifted forward by 10 months to give a better fit to the unemployment rate data.

That 10-month lag time is what produces the best fit between the two plots. Determining that best fit can be hard, because the consumer sentiment data is a lot noisier than the unemployment rate data. And the COVID episode screws up the correlation in a big way, albeit temporarily. So it is not a perfect model for unemployment, especially when the government puts a thumb on the scale.

What is clear from this chart is that, over time, changes in public mood eventually work their way into changes in the unemployment rate. The lag can be explained in part by how the mood changes eventually percolate down into spending decision changes of consumers. Also, hiring managers are humans also, and consumers, so changes in the public mood eventually come around to affect the collective mood of the hiring managers, which then shows up a bit later in the unemployment statistics.

The University of Michigan’s Index of Consumer Sentiment reached a peak (or a low in this inverted scaling) in April 2021. That ideally should have meant a bottom for the unemployment rate in February 2022, and we do observe that the unemployment rate bottomed out at 3.6% in March 2022, and has stayed within 0.1 percentage points since then. We should soon start seeing the effects on unemployment from the rapid deterioration of consumer sentiment, which has in part been a function of the high inflation numbers discussed above.

Some analysts are looking at the still-strong GDP data, and the unemployment rate sticking below 4%, and concluding that maybe this time we will avoid seeing an economic depression. That hope is misguided, because there is a perfect track record thus far of yield curve inversions bringing economic depressions every time we have one.

In the months following a yield curve inversion, there has always come a rise in the unemployment rate. It might take a while to start, but it always has come eventually. So for the economy to skip a rise in unemployment this time would go against the message of decades of data, and against the determination of the Federal Reserve officials to tame inflation, no matter what it takes.

You may have noticed that I used the word “depression” here. I do so with precise intention, and with the classical definition.

Contrary to what some modern day analysts believe, a recession is not a kinder-gentler form of a depression. A depression is any slowdown in economic activity of any duration. A recession is a component of a depression. So is a recovery. After the Great Depression in the 1930s, economists were cautious about using the word “depression” again, lest it conjure a mental image of something as bad as the Great Depression. So they started substituting the word “recession” when talking about a slowdown, leading to this modern mistaken belief that somehow a recession is a gentler event than a depression.

So, coming back to the leading indications described above, the bad news is that if you are an employee, working for someone else, your chances of getting laid off just went up. But the good news is that if you are an employer, who has not been able to find qualified applicants to come work for you, the pool of available people should start expanding soon, and those employers who can take advantage of this development can do well for themselves. That’s assuming your company can last through the impending downturn in economic activity and be ready to come out the other side.